If you happened to pass the Houses of Parliament over a recent bank holiday weekend, you may have spotted some of Simon Reed’s handiwork.

Simon is a co-founder of Extraordinary Spatial Performance, a company that uses detailed knowledge of architecture, events and digital projection to transform spaces with live, dynamic imagery. Together with his other co-founder David Keech, Simon has worked with a range of clients on all sorts of different installation, using the latest cutting-edge projection technology to deliver incredible, live visual feasts. He also documents these projects on film, with the help of some camera equipment from his local friendly hire company (ahem).

© Simon Reed (Portrait)

© Simon Reed (Portrait)

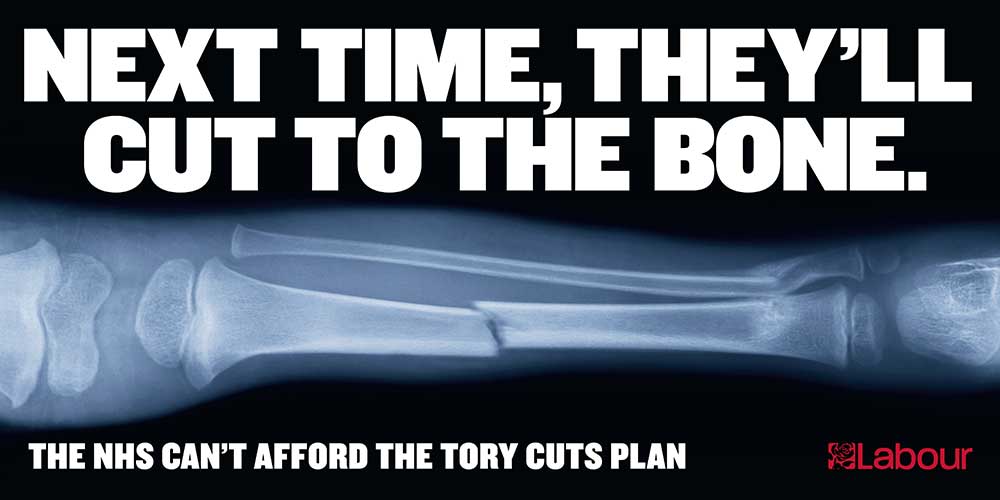

One of Simon and David’s most recent ESP projects was actually a pro bono piece – an amazing projection on the side of the Palace of Westminster in support of Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust and the Florence Nightingale Museum, celebrating International Nursing Day with enormous images projected across the width of the Thames.

© Photo by Jill Mead

© Photo by Jill Mead

You can check out a wonderful short video of the project here. We were hugely impressed, and were pleased when Simon agreed to chat with us for a ProFile to tell us a little more about ESP and the work he’s been doing. So, let’s get started!

Hi Simon – and congratulations on your success at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Trust! The images look incredible.

Thanks! With the lockdown, what we really wanted to do was offer something pro bono and do some really positive messaging. We reached out to the NHS Trust, and to our surprise they came back and asked if we’d like to do something.

© Photo by Jill Mead (The display was designed to commemorate the great work of the Trust, as well as celebrating International Nursing Day)

© Photo by Jill Mead (The display was designed to commemorate the great work of the Trust, as well as celebrating International Nursing Day)

The biggest challenge was that we didn’t realise the sheer scale of their original vision they wanted to achieve! It’s about 250 metres across the Thames, and they originally envisaged about 160 metres wide area of projecting against the Palace of Westminster. If we had done this commercially, a project of this complexity would have been a considerable budget to deliver.

We work with a lot of the technology manufacturers who are normally very positive in helping us out, but a combination of lock-down restrictions and only two working days notice to mobilise meant they were unable to find enough special projectors and lenses in time – so we just had to bite the bullet and hire in the only four 30,000-lumen projectors we could find. Working at pace with our clients, we had to adapt the graphics over the weekend, obtaining all the permissions we needed from the Port of London Authority and the Houses of Parliament – also getting the Houses of Parliament to switch all their lights off! We are grateful to the Florence Nightingale Museum who have since covered our hire cost.

© Photo by Ian Wallman (The bank of 30,000 lumen projectors at St Thomas Hospital)

© Photo by Ian Wallman (The bank of 30,000 lumen projectors at St Thomas Hospital)

The client approached us on the Thursday before the bank holiday weekend, and we were able to work at speed to pull it all together. We had a challenging moment late on the afternoon of the projection when the power failed, but a trip to Halo in Islington, 5 minutes before they closed, supplied us with the 100 meters of 3 phase cabling we required! We felt a huge sense of achievement and loved working with the NHS trust and Museum . We got a huge amount of interest as well as positive feedback from the Trust, and hospital staff. We are especially grateful to, Jill Mead, who took some lovely photographs. We hired a camera from Fixation and did a little 30-second video.

On the back of that, we’re in talks now with other London Boroughs to do other great things. It’s really worked out, and the technology providers who make these wonderful bits of projection equipment are really engaged with us. We’ve had a tremendous amount of attention on social media, so it’s something we want to do again for a great cause.

© Photo by Jill Mead (A tricky few days – but an extraordinary success)

© Photo by Jill Mead (A tricky few days – but an extraordinary success)

Going back to the beginning – how did Extraordinary Spatial Performance come about, what kicked it all off?

Both David Keech and I, met when we both worked at [architectural firm] Foster + Partners a number of years ago – I’m an architect and David is an industrial designer. After a while we went our separate ways, and for a number of years I worked for a number of developers and for AECOM, a multi-disciplinary practice involved with large scale developments and public realm including the 2012.Olympics in London and 2016 Rio Olympic Games – where I saw potential to transform spaces with large scale digital projections.

After leaving AECOM I started consultancy work with Keech Design, David Keech’s firm, who worked closely with technology manufacturers, including the latest generation of laser projectors. We instantly saw an opportunity to combine this technology within the built environment and said, “Hey, we’ve got something here.” We realised we could find uses for the projection technology that even the manufacturers hadn’t thought about. Stuart Harris, a projection mapping genius with a solid events background, joined us early on and plays a pivotal role in our delivery enabling us to do things we did not think of being possible.

The magic of the projection, if you get it right, is that it occupies and can transform a space, but then when it’s switched off, you’re instantly back in the room which reverts back to its original use and it leaves no trace. It doesn’t have this permanency – in today’s life, everywhere you go you’re sort of followed by merchandising screens. Piccadilly Circus is now in everybody’s living room, on everybody’s journey to work! It’s everywhere and it’s overwhelming, so we wanted to pare it down, step back and really play with the timings of everything. The result is a spectacle – it engages people, delights them, cheers them up, people interact with what we do.

So that was our starting point, and now it’s really taking off!

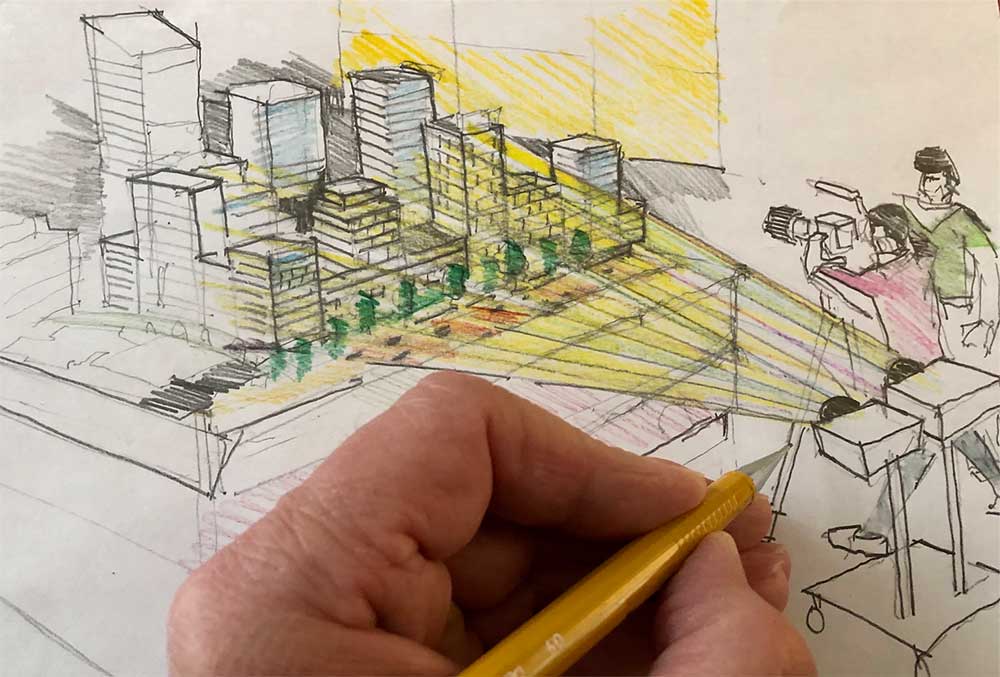

© Simon Reed (A preview of ESP’s proposal for American airports.)

© Simon Reed (A preview of ESP’s proposal for American airports.)

What kind of role do you take – do you direct the shoots and the overall projects?

At the moment, we bring together all our own practitioners – filmmakers, motion graphics experts, people with installation and projection mapping knowledge. Whilst David Keech and I are the founders, at this stage we’re still very, very much hands-on; I like to get involved right at the very beginning of a project, get the ideas going then, bring in all the disciplines to create something that works with the client’s budget and the space. That space may be an outside space like the Houses of Parliament, or it might be a tiny little room. We love being able to work at all scales and digital projection allows us to use every possible surface.

I like to get involved with the content; I storyboard, I sketch everything out. I’m learning the discipline of a filmmaker from our Director of Photography David Smith, and I now think in frames per second, looking at motion content in terms of what is the optimum duration, to have the biggest impact.

© Simon Reed (The team’s bespoke projector modelling software)

I scripted our showcase trailer for what we do, putting together a theme of a car driving by these colossal urban structures down by Southbank, which become animated and start telling the story of the spaces that we want to change – whether it’s a restaurant or a sports stadium spaces are our stage. This is currently the landing page on our website.

I really like to get involved with all stages of the creative process, and engage with clients all the way through to delivery. For the Houses of Parliament , Stuart and I set up in the afternoon, and we were the last one to leave the site at two o’clock in the morning!

© Simon Reed (It all starts with a hand-drawn sketch…)

© Simon Reed (It all starts with a hand-drawn sketch…)

Did you find it quite a learning curve, getting involved with filmmaking?

Absolutely. We’ve been very careful to work with the right people and to grow organically over the last few months; the people who make up our team are all exceptional in their trades. These are people who work together; we all read each other’s mind, we have all got the same temperament, and we respond to each other’s input to intuitively to fill in the gaps and make connections

© Simon Reed (The camera set up on location to capture an ESP project)

© Simon Reed (The camera set up on location to capture an ESP project)

Filmmaking is something that I’ve always been fascinated by, and to work alongside people like David Smith, who actually have the patience to equip you with such knowledge is a real privilege. It’s something that previously in a corporate world I wasn’t able to do – I was busy winning work and running big offices! As you say, it’s a massive learning curve, but I think we’re lucky in that we’re working with technologies that are evolving, and we’re evolving at the same pace along with them through our own research and development. We are a part of that collaborative process. Amazingly everybody is able to talk to each other in a simple, non-technical way to actually get results.

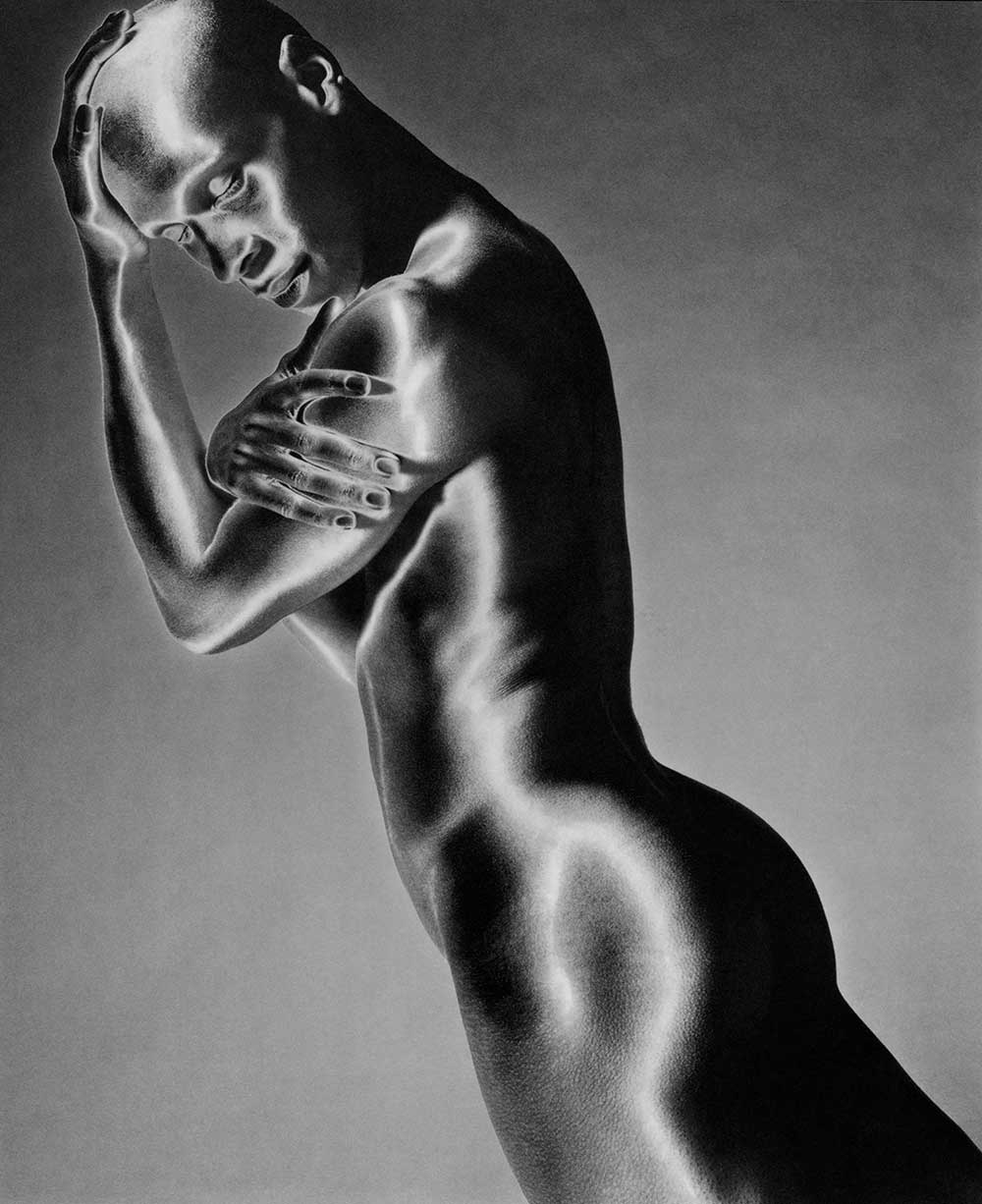

© Stuart Harris (Projection at Stonehenge)

© Stuart Harris (Projection at Stonehenge)

And it must be so satisfying to see those results come together – I’d imagine it could be almost addictive.

As an architect, I worked on the London Gherkin when I was at Foster + Partners, and that took five or so years of my life. It frustrated me – architecture is very process-driven, and whilst there are periods of incredible creativity, everything takes such a long time. What I like about the medium that we are working with now is that it is almost instantaneous – yes there are processes, there’s equipment, there are the frustrating gateways with the need for client sign off and that sort of thing, but once you’ve got through there is an immediacy of seeing results.

Very early on in the design process, we make little films of our ideas to convince our clients, to take a project forward, and we find that it’s infectious. We’ve never had a situation where we have sat down with a client and their jaws haven’t hit the table and said something like, “Oh my God, how can we do this?”.

It’s nice that it’s a quick process, and you see the results that are totally transformative to a building. And what’s most rewarding is that it’s not highbrow – you don’t have to have an arts background and a degree in architecture to appreciate it. This is universal, and when you see people’s faces and they engage in it, they get their phones out, they take photographs – they want to let others know about the joy they’re experiencing. That is a great, great feeling.

Simon Reed was talking to Jon Stapley. You can find Extraordinary Spatial Performance on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, as well as their website, espstudio.co.uk.