For more than two decades, Louise Murray has been a freelance photojournalist at the forefront of issues around ecology, nature, environmentalism and science. She has traveled from pole to pole, the Arctic to the Antarctic, to shoot critical stories on the natural world, and Fixation has been proud to keep her gear in tip-top shape while she does it.

Louise is also a keen diver – a passion she shares with Fixation’s Mick Edwards whom she helped get his first drysuit – and she brings that love of the underwater world into her photography, where she has thoroughly explored the limits of underwater photography, not to mention her own endurance. We’ve featured some of her amazing stories on the blog before.

As Louise was resting between projects a couple of weeks ago, we managed to find time to chat with her about her career, travels and photography. Join us as we learn all about what it’s like to photograph in minus-40 temperatures, how Louise got deported from Canada, and what it is that keeps her coming back to diving…

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

Thanks for chatting with us, Louise! What have you been working on lately?

I had a month in the Philippines in March, and there was a whole lot of marine science stuff I was doing, including a piece for The Economist. I was also photographing thresher sharks – they are these very beautiful, quite elusive sharks, and the Philippines are one of the rare places you can reliably see them. I did some travel pieces, one just published that was about macro and macro lighting with lots of close-up photography.

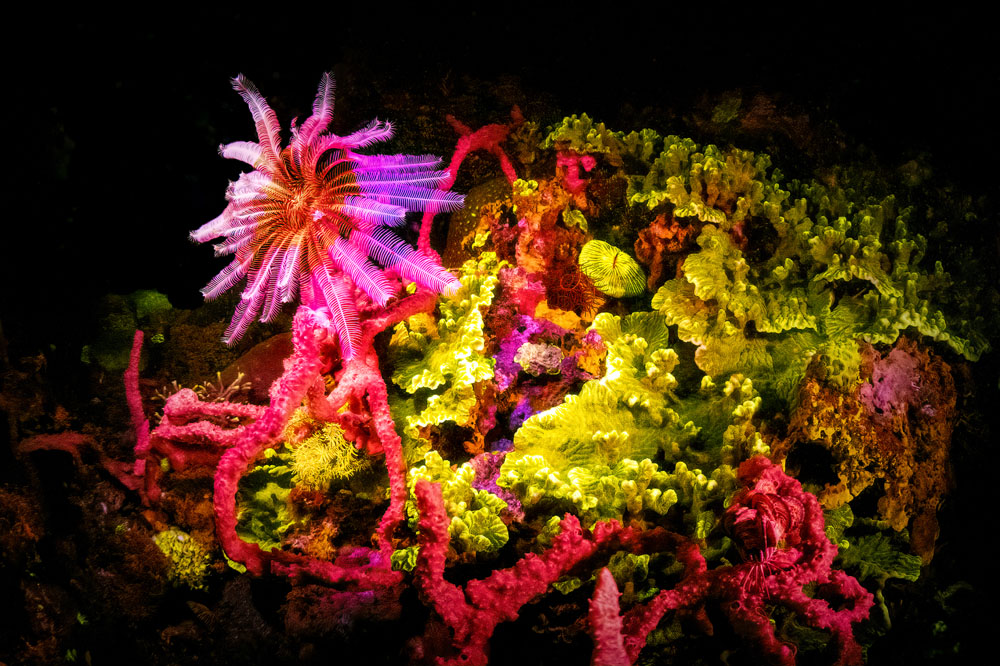

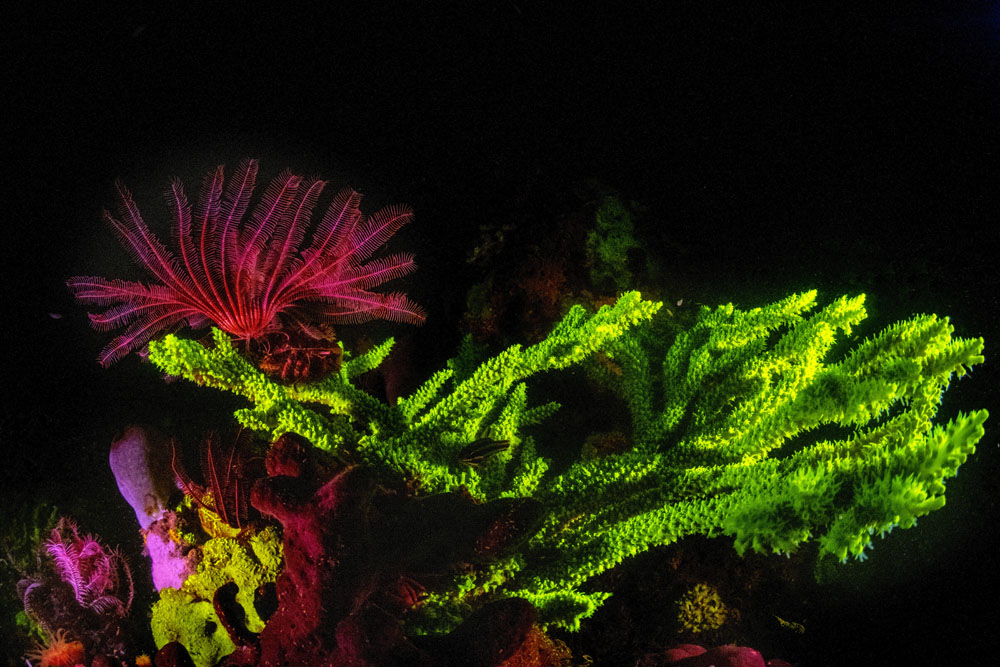

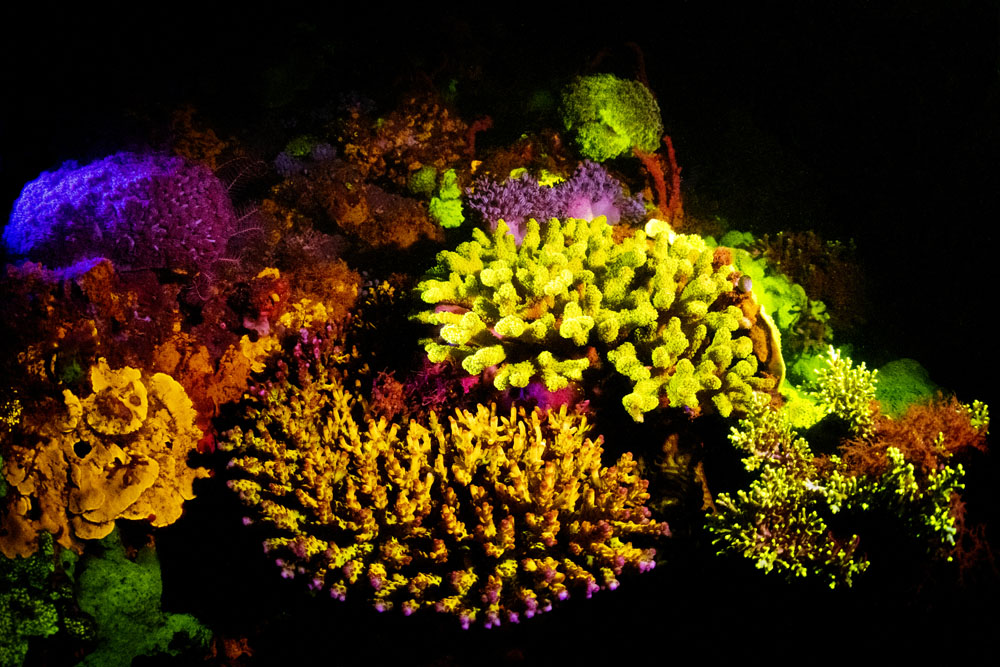

I was also shooting fluorescence in marine life. You shoot it at night stimulating hidden pigments in the corals with blue light – I’ve been trying to get wide-angle shots for a couple of years now and finally succeeded. I think the Nikon D850 really made a difference, and the more powerful lights – it’s been a long time coming! I shot a funny little timelapse of the three of us trying to work together in pitch blackness with blue lights, trying to make the shot.

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

That sounds quite difficult…

It’s very difficult. You start off on land, in daylight. You need expert divers with you who understand what you’re trying to do, and you have to have a full-on briefing before you even start. Often the local guide who’s with you has never experienced this and he doesn’t know what to expect, so you have to cover all this in your briefing. And then still it ends up being a bit of a nightmare as everybody works out how to work together in the dark without getting nailed by spiny, stingy urchins that come out at night.

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

Of course, you’ve done lots of marine work if I remember correctly?

Loads of marine stuff, loads of Arctic stuff, loads of Antarctic stuff. I’ve also been doing a lot of work with robots over the last two years, and they’re always challenging. Photographing

them for stories about robotics – so whether that’s autonomous vehicles, or robots in horticulture, or robots in forensic science conducting autopsies. I went to Switzerland for that one. It’s a huge variety of different things, most of which are not on my website because I’m too lazy to update it!

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

Do any projects stick out as your favourites?

I think this fluorescent stuff recently. I love diving, so I’ll take any excuse to do it. It looks like I’ve got another couple of big underwater projects coming up – for most of October I’ll be back in the Philippines, which will be great fun. Then back to Baja Mexico in November.

Sounds awesome! Are you hunting for anything in particular?

I’m doing an environmental story on the world’s biggest fish in the Philippines, then freediving with hunting Striped marlin in Mexico.

A lot of what you have covered in the past concerns ecology and climate change.

It’s been a while since I’ve written about climate change, but yes. I had a picture on the front page of the Guardian illustrating climate change. It’s a shot you can only get at a certain time of year; when the sea ice is melting, it melts during the day then refreezes at night. You get protruding blocks of ice forming where it has broken up and refrozen, and in early May those start to melt and drip during the day in earnest. If you get there at the right time and then shoot into the sun, you produce an image with a concept of sun, heat, and melting ice that encapsulates what is happening with the climate emergency in the Arctic. That’s why those particular sets of pictures do very well.

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

Are there other aspects of the climate emergency you would like to cover?

I would kill just to be back up in the Arctic, but I got deported from Canada. You have to try very hard to do that. I would very much like to be able to go back up to Nunavut, where I used to lead expeditions helping film crews make feature-length movies about wildlife up there. I was working illegally without a work permit. So I rocked up a year or two later thinking, “Well that’s all done and dusted, and now I’m here with several thousand pounds of commissions.” But the immigration officer didn’t see it that way, and they held me in immigration and sent me back on the next plane, which wasn’t very pleasant. Haven’t been back to Canada since.

So where else might you head instead?

I had to turn it down this year, but the Siberian Ice Marathon, where people run across the frozen surface of Lake Baikal. It clashed with the Philippines this year, but I’ll be going back next year. It’s great fun.

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

You do enjoy the cold, don’t you?

Once you’ve got the right clothes. It’s down to having the right gloves and the right boots. I’ve worked in minus-40 with the Danish military – that was an amazing job. In Eastern Greenland they have a unit called the Sirius Patrol – pairs of guys patrol with dog sleds over that uninhabited part of Greenland, right up to the extreme north to protect Denmark’s sovereignty over the land. That was an amazing cold shoot – quite painful, but not impossible.

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

I can’t even imagine how you’d take photos in those conditions.

You have to have a lot of batteries inside your coat. That’s the key thing. When we used film it used to freeze, but with digital, it’s the batteries. You can practically see the battery gauge going down.

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

I suppose digital has unlocked a few interesting possibilities in your line of work.

The marine stuff is much easier to do now than it ever used to be, because we used to go down with a tank of air and one roll of film, which was 36 or 37 frames if you were lucky. To change the film, you had to come back up, open up the housing, open up the camera, change it, and then go back down. And this is dangerous, because you don’t want to be popping up and down when you’re diving. You can’t do it repeatedly – it isn’t safe. So it’s marvellous to have high-capacity cards and be only limited by however long your air lasts. And the poor bastards who have to dive with me tend to find out just how long I can make a tank last!

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

© Louise Murray

What is it that keeps you coming back to diving and underwater shooting?

Well, it’s very calm down there. And no matter where you dive, even if you’ve dived somewhere a thousand times, it is still quite possible to go down and see something that you’ve never seen before. It still happens to me, after all these years working underwater – I can still go on a dive and see a behaviour or a creature that is entirely new to me, though not new to science. Although when we go to Indonesia in October, it’s possible that we’ll see stuff that is new to science!

We look forward to finding out!

Louise was talking to Jon Stapley. See more from Louise at her website: louisemurray.com